Monograph

A brilliant artist faded into obscurity

A brilliant artist faded into obscurity

Genesis of a discovery

It is extremely rare to lose all trace of an artist, especially one who made a brief impression during his own era. Considering that this artist lived in the 20th century, such a disappearance becomes even more curious when one takes into account publications by numerous art historians, the increasingly well-structured sales of Art to the general public, and of course the vast resources offered up by the Internet. Collectors or historians occasionally make lucky discoveries, but they almost always pre-date the 19th century. Moreover, talented painters who “re-emerge” have not really disappeared, but simply been forgotten.

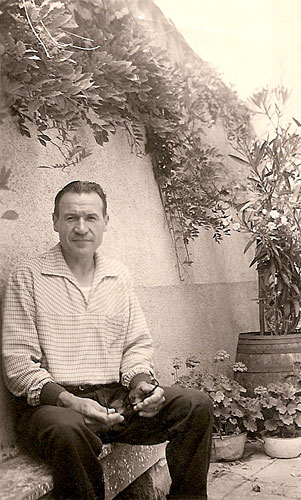

René Teil is therefore an unusual case. He simply vanished without trace after three quarters of a century of a life dedicated almost entirely to painting. He enjoyed an extremely respectable career, nurtured by the praise and encouragement of some of the most renowned art critics and artists of the era, a career championed by prominent art dealers and one that was ultimately fulfilled through regular displays of his work in Salons and exhibitions in the most prestigious Parisian galleries, periodically alongside already well-known contemporary artists. After Teil’s death in 1985, the trail went cold: there are no bibliographical references, and he has never appeared in any auction database. Absolutely nothing. In spite of the exceedingly high quality of his work, his unquestionable poetic talents and professional success, Teil simply vanished.

René Teil is therefore an unusual case. He simply vanished without trace after three quarters of a century of a life dedicated almost entirely to painting. He enjoyed an extremely respectable career, nurtured by the praise and encouragement of some of the most renowned art critics and artists of the era, a career championed by prominent art dealers and one that was ultimately fulfilled through regular displays of his work in Salons and exhibitions in the most prestigious Parisian galleries, periodically alongside already well-known contemporary artists. After Teil’s death in 1985, the trail went cold: there are no bibliographical references, and he has never appeared in any auction database. Absolutely nothing. In spite of the exceedingly high quality of his work, his unquestionable poetic talents and professional success, Teil simply vanished.

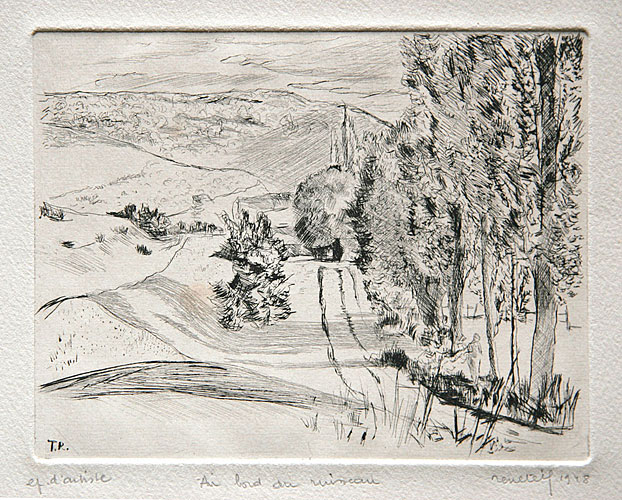

This is therefore an attempt to understand the reasons behind Teil’s disappearance and to have his work reinstated within the relevant framework of the History of Art. We seek to introduce enthusiasts and art historians to this authentic, creative artist, who remains unheard of today. In spite of this disappearance, or perhaps because of it, the most magnificent and most important traces of him remain: an extraordinary “backroom studio” containing approximately 450 pieces – oil paintings, sketches, watercolours, etchings – all perfectly preserved, spared from dissemination either through disinterest or indifference amongst the heirs of an artist erased both from memory and the market.

In May 2008 we receive a letter from a stranger who is trying to contact us because her grandfather, a painter who has been dead for 23 years, was a friend of André Dunoyer de Segonzac (for all names refer to the index entitled “Surrounding Teil”). She has just inherited his works and is requesting our advice. Several artefacts of past exhibitions are included with her letter, in which the names of prestigious art galleries seize our attention.

In May 2008 we receive a letter from a stranger who is trying to contact us because her grandfather, a painter who has been dead for 23 years, was a friend of André Dunoyer de Segonzac (for all names refer to the index entitled “Surrounding Teil”). She has just inherited his works and is requesting our advice. Several artefacts of past exhibitions are included with her letter, in which the names of prestigious art galleries seize our attention.

Included with the letter are copies of his work (1940’s printing quality!) that capture our interest and somewhat intrigue us. Our curiosity is fully ignited when a quick search for René Teil does not produce any results whatsoever.

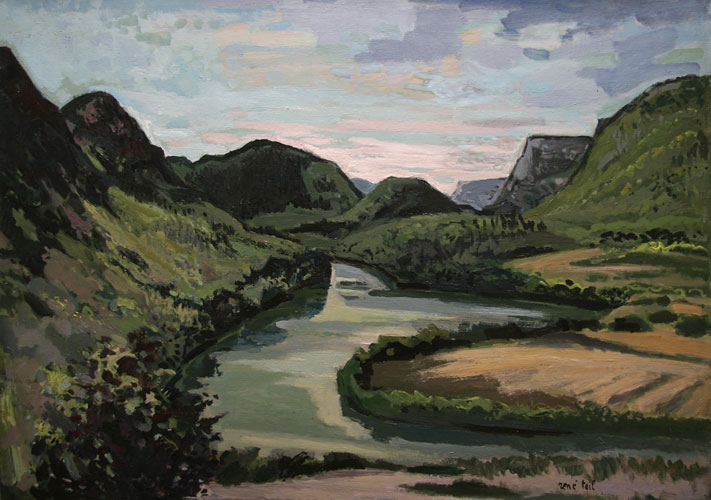

We suggest a visit to the artist’s granddaughter, who lives in south-western France. Perhaps the next time we are in the area, we could come and view the artwork in question? In December 2008 we finally make the trip. We are truly amazed by what we find: in one afternoon we view almost three hundred works that display a style that is completely unique, straight-forward, sober, demanding and devoid of overindulgence. Throughout an extensive body of work, this passionate painter’s cohesive and consistent point of view emerges in his attempts to capture the ephemeral light of a landscape, the pulsating air that surrounds a still life, the mystery of a portrait model’s hidden personality and the rush of emotion from the beauty that inspires him.

The quality of all the work we see that day is occasionally inconsistent. However, even the “less accomplished” pieces contribute to a compelling case, bearing witness to the artist’s authenticity, the creativity of his research and the stability of his own personal standards. Teil’s aesthetic education and the inspiration drawn from his predecessors are quite clearly revealed: Dunoyer de Segonzac, of course, but also Marquet, Matisse and Vlaminck. We sense from the outset that Teil was a humble, unobtrusive artist. His work also indicates that he was an extremely cultivated man. We are quite baffled as to how over three hundred works of this quality could have remained unearthed, forgotten even, albeit carefully and reverentially preserved in the heart of the Gers countryside. If this painter’s name has disappeared without trace, could the only explanation be that we have botched our research? Not so. The facts plainly reveal that the name René Teil has disappeared from all accounts of the 20th century History of Art.

Several months later we go and see a large number of other paintings that have been kept by the painter’s daughter-in-law, who lives in Paris. The same sense of originality and honesty inherent in Teil’s work convince us that these compositions are indeed originals, in the aesthetic sense of the word. This conviction, combined with the strength of evidence, would ultimately lead us to extensive information retrieval, the initial results of which are provided below.

The life and career of René Teil

1910-1928

René Teil was a child of the Seine et Marne region, before becoming a painter of the Seine et Marne. He was born in Lieusaint on 10th July 1910 into a very poor family. His mother was a village farm worker from Brittany and his father was an unskilled labourer from the Auvergne region. Teil was the eldest of five brothers.

After the premature death of his father in February 1920 (due to toxic gas inhalation during the First World War), Teil, along with his four brothers, is adopted by the social services of the Melun Court system in 1921 and thus becomes a ward of the State. Talented artists often realise their potential at a young age and such is the case with René Teil; at age thirteen he receives his first box of paints as a gift from his teacher, who, by reason of the boy’s adoption by the State, officially becomes his father. He has already noticed young René’s potential.

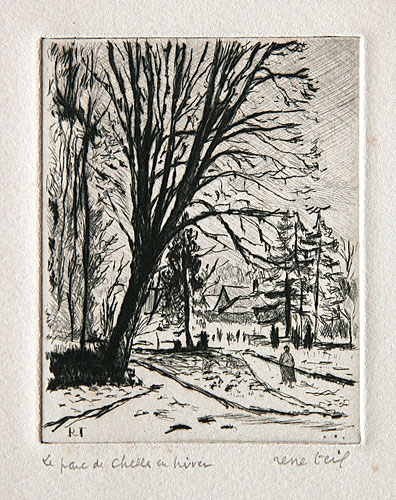

After his mother remarries in 1923, Teil leaves Lieusaint for Moissy-Cramayel, several kilometres to the east. In 1926 he enters the Ecole Normale, where he studies for three years. He takes up his first teaching position in Brie-Comte-Robert in 1930, where he meets his first wife, Denise Goujon. She is also a teacher. They marry in Chalon-sur-Saône on 11th August 1930. They produce a son, André, who passed away prematurely in 1986. René and his wife Denise spend their entire professional careers teaching at the Ecole de la Villeneuve in Chelles in the Seine et Marne region. As educators they are both appreciated and respected, teaching there until 1965. This region has a lasting influence on Teil’s life: he produces numerous paintings and watercolours that capture the murmuring waters, the sunlight-dappled the trees, the small dams and hidden streams amongst the villages and towns of Marne and Petit Morin, on the banks of the river Seine.

1928-1940

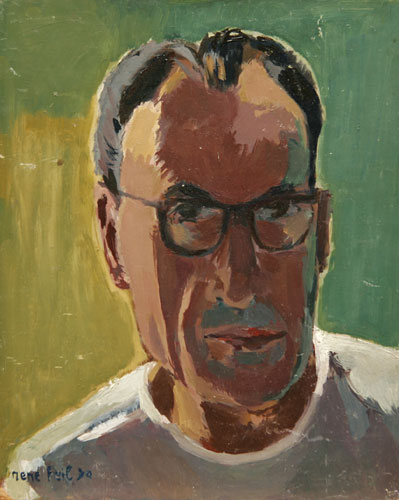

From 1928 onwards, Teil’s body of work and his aspirations as an artist become established. Two signed documents confirm that Charles Jacquemot was his first master. The influence of this excellent painter, nowadays unheard of, although highly documented in Art History and secondary market data banks, recurs throughout Teil’s creative career. Jacquemot worked at the Académie Julian in Paris. He met Matisse there, and also knew Marquet; they often painted together on the banks of the Seine. René Teil’s entire body of work displays a clear, albeit subtle hint of influence from these three artists. It is also likely that Jacquemot was responsible for introducing Teil to André Dunoyer de Segonzac, whose work had such a profound effect on Teil’s entire artistic career. Dunoyer de Segonzac’s benevolent, protective appreciation of Teil’s undeniable talent proves to be long lasting, affectionate and loyal. In the early1930’s René Teil attends the Académie Scandinave to study under Othon Friesz. Teil’s first sketchbooks date from this era. Delightful sketches of his young child are dashed onto the pages in Teil’s swift, mischievous hand: “Didy l’affamé” (Didy starving hungry), “Didy et le p’tit ours” (Didy and the little teddy bear) or even “Didy la grippe” (Didy with flu), dated 10th February 1935. That same year, a self portrait in pencil, completed at just age 25, already displays Teil’s gift for clarity and conciseness, through an economy of means unique to all master artists.

These sketchbooks also contain personal musings, as well as Teil’s private analysis of his own work. The following text from the same period, in its original, unabridged form, is the only theoretical discussion about Art that Teil recorded in his entire life; even then it was purely for his own use:

Art is but a language. An artist uses sounds, words or fine art to express what he feels when experiencing certain aspects of nature. The value of a work of art lies in the significance of the language used, which is driven by the emotion he feels. In the same way that even a piece of expressive music is not the exact reproduction of the sounds experienced, a painting can never be an exact reproduction of nature, and by nature I mean a landscape, a group of objects or a portrait of living beings. (Editor’s note: quoting Raoul Dufy) “Above all, painting is an art of the eyes and senses. Its foundation lies in the most beautiful colours, the most beautiful lines imaginable; beautiful when they stand alone and further embellished by their correlation and their harmony. It is therefore a very practical form of art. Perfection begins with the painter’s choice of brushes and palette”, Dufy continues: “Painting is an art of spontaneous creation; I would go further and say that the artist is simply an intermediary between the inspiration he wishes to convey and the resources provided by his own everyday existence. He interprets and translates both. The artist cannot alter his inspiration; to modify it would be to betray it; instead, it must be rendered as is”. Painting is therefore essentially striving to use fine arts to translate the feelings of a man with regards to life. It is clear that a painting is that much more beautiful and more accomplished if the feelings of the painter are incisive and more acute. In his diary, Delacroix recorded the emotion that seized his artistic sensibilities when his model knocked at the door of his studio. First and foremost, the woman that was about to undress before him would offer up the inspiration of shapes, lines and colours, while remaining vibrantly alive as the embodiment of Woman. Waroquier wrote: “Paint with love, paint with the feelings that stimulate the mind and body in the very face of life itself. Seize life assertively, with every fibre of your being, with a tumultuous passion or a profound calm, with audacity, with rage and anger, or with restraint, consideration, meditatively; with sensuality or with faith and abstinence; paint apprehensively or in a state of bliss, but never using sleeve protectors”.[1]

Throughout the artistic endeavour, you must live the object being painted, in a deep, spiritual sense. Feel it in your body and use your hand as the instrument of that determined or reflective mind; use that hand to caressingly shape a woman’s skin, weave the intermingled or blended colours of a woollen garment, harden the texture of a metal, or crudely fashion a boulder’s geological formation. The artist must paint the angry man in a state of rage, levitate when painting a saint, or fall to his knees should he dare to create God Himself.

After these ambitious words that clearly define how the painter must approach his subject, would you prefer a more informal image, although no less authentic than the previous ones? Renoir remarked: “I consider that my painting is finished when I get the urge to smack the buttocks of those remarkable bathing beauties”. (sic).

All works of art worthy of being referred to as such must convey the strength of a feeling, or passion. The methods used by the artist must interpret his thoughts. The man must be felt through the canvas; the work must be a cry that can be heard by all. These initial characteristics will quickly determine whether a painting contains any artistic merit. The work can only be valuable if it expresses something human; it must be nothing like those tentatively painted copies of nature, devoid of character, that resemble badly taken colour photographs. A shape in a painting is not just simply a coloured space; it must represent a piece of fruit, a magnificent product of the earth, destined for the delight of man.

The colours used must recreate and embellish its shiny skin, its smooth, cold, tightly packed seed and beneath the veneer of colours that speak to the ripeness of the fruit, you should be aware of its coarse, succulent flesh. Through your eyes it speaks to your stomach.

A painting must appeal to the eye through its harmonious selection and consistency of colours, the balance of shapes and lines, the distribution of shadows and light, and through the gentleness and variety of its shaded areas; then, once it has assuaged your senses, it must glorify an idea, a feeling. This is what must be demanded of a true work of art.

The artist’s very essence must emerge through the subject matter, through the work itself. Van Dongen only achieves greatness when his paintings make us experience the childish precociousness of the middle classes or the bloom of youth; Dufy’s artistry only stands out when he conveys, through his colourful arabesques, the love of life, the love of grace and honesty, the passion that embodies joy. Vlaminck uses very few picturesque details in his pure white, stormy landscapes, so inhospitable and devoid of human presence, underscoring man’s struggle against an all too often triumphant nature.

The painter, through his canvas, conveys his reactions to nature and his interpretation of life. Moved by inspiration, armed with his paintbrushes and paints, he will free himself, shout of his overwhelming joy or violent grief, he will communicate to others the raw pain of his feelings.

A genuine struggle then, between this feeling, this passion that wishes to assert itself and an oftentimes unruly subject matter. It is from this occasionally drawn out, powerful, tragic duality that the work of art will emerge, grimacing.

Grimace is the very word that the connoisseur Beyson uses when he tells artists to “make the subject grimace!” Grimace does not mean deface in this instance, but rather affirm, clarify the characteristics, increase the size, plump the mouth, expand the quivering nostrils of the person who hungers for life; see, seize, grasp the object and captivate the audience through that distorting and expressive mirror that is the artist’s soul.

Understand painting? It cannot be understood, it exists beyond the realms of logic. It is not a problem, an equation of lines or colours offered up to the mind, or to the intellect. It touches the heart through a cry addressed to our senses. When standing before a work of art, if an artist’s emotions are truly present you should feel forcibly seized, shaken and literally gripped by genuine anxiety. I know of no-one who remains indifferent when standing before Géricault’s Naufrage de la Méduse (Raft of the Medusa) or Delacroix’s La Liberté conduisant le peuple (Liberty leading the people). Standing before a Cézanne or a Corot your chest expands, you inhale deeply through your nostrils, your eyes open wide to absorb the freshness, the life, the complexity, the lightness of the work!

Your mouth waters at the sight of a still life by Vlaminck or Matisse, a shiver runs through your loins when you stand before Courbet’s Les Dormeuses (The Sleepers) or Titien’s Les Vénus (The Venus’s). Life, this is what the mortal painter tries to immortalise. His entire body of work must simply be an affirmation of life, an irresistible hymn to life itself!

Do not simply glance quickly and condescendingly at the piece. If the work managed to attract your attention, move closer and allow an honest conversation to take place between you and the painting, free from any hypocritical convention. It will speak to you through its subject matter, its composition, the harmony of its colours, it will calm your weary nerves, bring you joy and Faith; you will be able to appreciate fully that life is beautiful and worthy of being lived.

Regular companionship with works of art will refine your senses. “You will no longer indifferently observe firm, rounded hills that are reminiscent of women’s breasts” stated Giono, “you will be even more aware of nature’s boundless beauty as you stand before a green and grizzled mass of trees or oily, dense anemone petals. In this blissful state you will find a way to continuously strengthen your Joy”.

[1] Literal translation: in French “manches de lustrine” suggests someone with low ambitions and a dull existence who does not try to extend themselves.

Remember that René Teil was only twenty-five when he wrote this text.

1940-1950

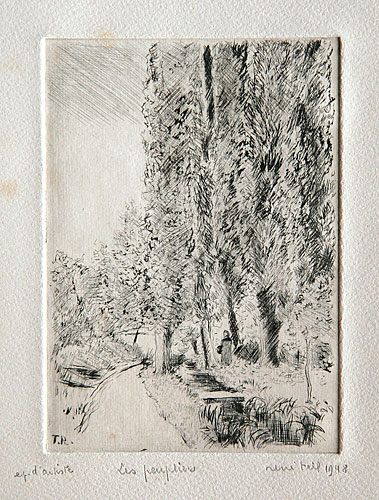

For the first time in 1941 René Teil is invited to an “official” event: he participates in the Salon d’Automne (Autumn Exhibition), displaying two compositions “Brou sur Chantereine” and “Vue de Chelles” (View of Chelles) (footnote: Salon d’Automne Catalogue 1941, page 121). Art critic Pascal-Levis’s review in “Les artistes d’aujourd’hui” (Artists of Today) states: “This artist’s works reveal an excellent landscape painter (…). Beautifully resonant greens and a broad sense of space provide much emphasis and dimension (…) René Teil possesses a robust, genuine ability, a handsome technique combined with a consistent talent.” To our knowledge, it is the first time that a renowned Art critic expresses an opinion on Teil’s work. This first Salon d’Automne will also be a symbolic milestone for Teil, who now finds himself amidst an illustrious circle that will considerably expand his prospects; in fact, all those that either have or are to influence Teil’s work are members of the 1941 Salon: not only Matisse, Marquet, Jacquemot, Dunoyer de Segonzac, but also Cavaillès, Caillard, Brianchon, Planson, Legeult, Limouse, Oudot and Terechkovitch; the eight painters that are part of a group later named “The Painters of Poetic Reality”, and who will soon cross paths with Teil’s destiny and career. More on that later.

In 1942, Teil exhibits in Paris at the Galerie Charpentier alongside other painters and once again participates in the Salon d’Automne. However, his career only really takes off in 1946, when Teil receives André Dunoyer de Segonzac’s first endorsement after a visit to show him his work. Professionally speaking, the high regard of a Master, whose notoriety and prestige are considerable at the time, yields a valued and long-lasting guarantee of the young artist’s talent; from a personal standpoint, an enduring, affectionate and protective relationship, documented through numerous letters between the two artists. This correspondence will also reveal an authentic, candid reflection of the lives of these artists, for whom figurative classicism became something of a crusade led by the “remaining survivors” amidst the artistic circles of influence of their time:

In 1942, Teil exhibits in Paris at the Galerie Charpentier alongside other painters and once again participates in the Salon d’Automne. However, his career only really takes off in 1946, when Teil receives André Dunoyer de Segonzac’s first endorsement after a visit to show him his work. Professionally speaking, the high regard of a Master, whose notoriety and prestige are considerable at the time, yields a valued and long-lasting guarantee of the young artist’s talent; from a personal standpoint, an enduring, affectionate and protective relationship, documented through numerous letters between the two artists. This correspondence will also reveal an authentic, candid reflection of the lives of these artists, for whom figurative classicism became something of a crusade led by the “remaining survivors” amidst the artistic circles of influence of their time:

(…) I think of young people like you, extremely talented – honest – creating authentic work – no bluff – and genuine – living in an era of trickery and lies in the art world. You deserve double the credit, remaining pure by using the example of Cézanne, who experienced hostility from academia and their “official” methods, which form the antithesis of True art, and who was able to persevere throughout his entire life. Our era is subjected to a double falsehood: the lingering academic formula of the Beaux-Arts and the neo-Cubist movement that is supported by the “officials” and is equally as false and formulaic. The truth is far simpler. Jean Fouquet, Poussin, Chardin, Corot, Cézanne and even le douanier Rousseau taught us this lesson.

It was the line, pure and true. Believe me, all that trickery, bluff and publicity will prove meaningless over time.

With the greatest respect for both yourself and your work.

Segonzac.

(Post card addressed to René Teil on 4th January 1947).

In 2009, Marc Lacruz, who was Teil’s last art dealer, and also his neighbour and friend in Beaujolais for many years, once again evokes the overwhelming admiration Teil felt for André Dunoyer de Segonzac throughout his artistic life; “often, in summer, he would disappear for several weeks without saying where he was going, but I knew that he was off to St Tropez to paint in the same places as Segonzac. He would set up 50 metres away from his easel without really daring to talk to the renowned painter, who was nonetheless his friend, and would paint quietly nearby”. It is also Segonzac who will introduce René Teil to the art dealer Jean Baignières. This turns out to be an important encounter, because from 1947 until 1981, Jean Baignières is responsible for organizing all of René Teil’s exhibitions. This dealer, a personal friend of Paul Durand-Ruel, was the son of the artist Paul-Louis Bagnières, who studied at the Gustave Moreau studio and was friends with many of the painters he met there, including Marquet and Matisse. It is likely that he also knew Charles Jacquemot, Teil’s first Master, because they both worked at the Académie Julian at the same time. Thus, a network of talent and universal aesthetic conviction is gradually being formed around Teil. As encounters occur, artistic connections are established that will colour his entire career as an artist. Devoted friendships and a certain amount of good humour in the stubborn resistance to shifting trends, whatever they may be, seem to exemplify all these artists and art dealers. In addition to René Teil, whose work and talents he would promote for thirty four years, Jean Baignières was also Oudot’s art dealer throughout his entire career. Caillard and Brianchon, Cavaillès, Planson, all friends of Oudot, also benefited from his support and services.

In 2009, Marc Lacruz, who was Teil’s last art dealer, and also his neighbour and friend in Beaujolais for many years, once again evokes the overwhelming admiration Teil felt for André Dunoyer de Segonzac throughout his artistic life; “often, in summer, he would disappear for several weeks without saying where he was going, but I knew that he was off to St Tropez to paint in the same places as Segonzac. He would set up 50 metres away from his easel without really daring to talk to the renowned painter, who was nonetheless his friend, and would paint quietly nearby”. It is also Segonzac who will introduce René Teil to the art dealer Jean Baignières. This turns out to be an important encounter, because from 1947 until 1981, Jean Baignières is responsible for organizing all of René Teil’s exhibitions. This dealer, a personal friend of Paul Durand-Ruel, was the son of the artist Paul-Louis Bagnières, who studied at the Gustave Moreau studio and was friends with many of the painters he met there, including Marquet and Matisse. It is likely that he also knew Charles Jacquemot, Teil’s first Master, because they both worked at the Académie Julian at the same time. Thus, a network of talent and universal aesthetic conviction is gradually being formed around Teil. As encounters occur, artistic connections are established that will colour his entire career as an artist. Devoted friendships and a certain amount of good humour in the stubborn resistance to shifting trends, whatever they may be, seem to exemplify all these artists and art dealers. In addition to René Teil, whose work and talents he would promote for thirty four years, Jean Baignières was also Oudot’s art dealer throughout his entire career. Caillard and Brianchon, Cavaillès, Planson, all friends of Oudot, also benefited from his support and services.

In 1948, René Teil’s first solo exhibition is held at the Galerie Chardin. In his letter dated 25th November, André Dunoyer de Segonzac offers up several pieces of advice regarding the display and presentation of the selected artwork. Letters between the two painters at the time, as well as the comments Teil makes in his notebooks, are interesting to read because they speak of “craft” as much as aesthetics: ”Let the critics say what they want! The only thing that matters is what you felt so intensely”, Segonzac advises him. Regarding the painting entitled “la Grande Forêt” (The Great Forest), the elder painter recommends: “It is really beautiful, really powerful. But be wary of using emerald green. It is a colour that does not age like the others. It does not fade!

Use greens that are made of ultramarine and cadmium lemon or cobalt and cadmium yellow. Your greens will age like your other colours… Use red ochre rather than Venetian red…Don’t use too much oil! There is already too much in the tubes”. Later, in November 1951, on his way to buy paints, René Teil meets André Dunoyer de Segonzac on the rue des Beaux-arts, where they discuss their craft: “Buy Blockx! They are the best oil paints. Get Rowney for your watercolours. Signac did a lot of research on colours, their chemical reactions, gave me advice that I am passing on to you….”

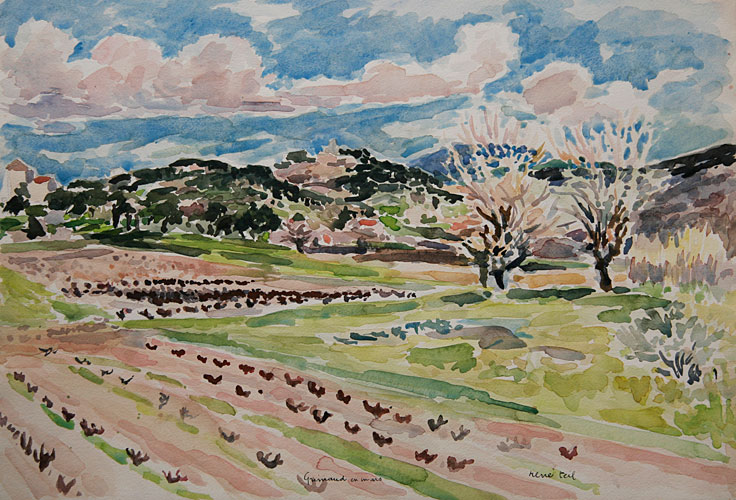

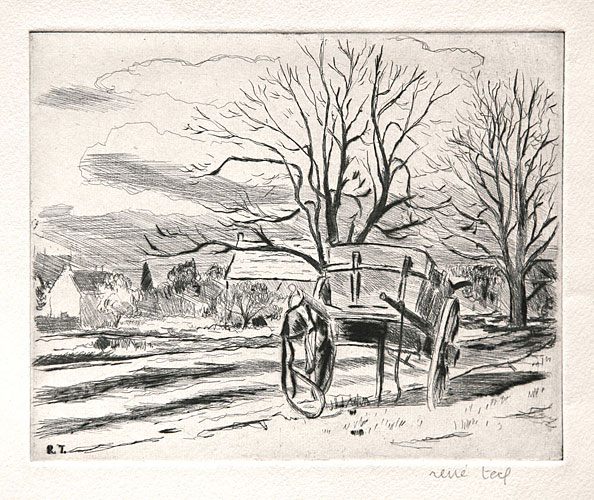

The artwork displayed at the Galerie Chardin seems to have enjoyed relative success. In fact it drew a reaction from Jean Bouret, the art critic. In the “Arts” review, dated 17th December 1948 he writes: “this painter conveys a deep and most wonderful connection with nature, a love for the contours that he presents …colours and forms play off each other harmoniously”. Guy Dornand, the renowned art critic, praises Teil in the “Libération” publication, dated 11th December: “this magnificent landscape artist, whose plough scenes smell of the earth, whose greenery and undergrowth exude the fragrance of humus-rich soil”. Furthermore, following this exhibition, Guy Dornand will present Teil at the 1949 Prix de la Critique (Critic’s Choice), which was actually won by André Minaux (winners in 1948 were Bernard Buffet and Bernard Lorjou). It should also be noted that from this first solo exhibition onwards, Guy Dornand’ s respect, support and friendship remains a continuous mainstay throughout Teil’s entire life.

The artwork displayed at the Galerie Chardin seems to have enjoyed relative success. In fact it drew a reaction from Jean Bouret, the art critic. In the “Arts” review, dated 17th December 1948 he writes: “this painter conveys a deep and most wonderful connection with nature, a love for the contours that he presents …colours and forms play off each other harmoniously”. Guy Dornand, the renowned art critic, praises Teil in the “Libération” publication, dated 11th December: “this magnificent landscape artist, whose plough scenes smell of the earth, whose greenery and undergrowth exude the fragrance of humus-rich soil”. Furthermore, following this exhibition, Guy Dornand will present Teil at the 1949 Prix de la Critique (Critic’s Choice), which was actually won by André Minaux (winners in 1948 were Bernard Buffet and Bernard Lorjou). It should also be noted that from this first solo exhibition onwards, Guy Dornand’ s respect, support and friendship remains a continuous mainstay throughout Teil’s entire life.

1950-1960

In 1952 René Teil presents another solo exhibition at the Galerie Allard. One of the paintings, entitled “le champ d’avoine” (Field of Oats) is purchased by the State (it is currently on display in the town of Rodez in the Aveyron Prefecture). Teil’s artistic career is now fully underway…

In 1952 René Teil presents another solo exhibition at the Galerie Allard. One of the paintings, entitled “le champ d’avoine” (Field of Oats) is purchased by the State (it is currently on display in the town of Rodez in the Aveyron Prefecture). Teil’s artistic career is now fully underway…

He participates in a group exhibition that brings together the landscape artists André Planson, Roland Oudot, Christian Caillard, Jules Cavaillès, Arthur Farges, Poncelet and Gabriel Fournier. This exhibition tours Montpellier, Nimes, Toulouse and Casablanca. From 1949 onwards, several of these painters will be a part of the group known as the “Painters of Poetic Reality”.

In February 1954, Teil exhibits a painting at the Pavillion Marsan within the context of the “E.Othon Friesz Painting Grand Prix” entitled “Devoirs de vacances” (Holiday Assignments). Three months later he is among the young talent showing in an exhibition held in Crécy-en-Brie (now called Crécy-la-Chapelle). E.-R. Collot, a columnist for Le Figaro newspaper, provides relevant context from that era with his commentary, dated 26th February 1954, deeming this exhibition one of the “most compelling to have been held for a long time in the Ile de France region”. René Teil shares this honour alongside some of the most well known artists of his time such as André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Suzanne Valladon and Raoul Dufy.

Did the “victory march” begin to play in his workshop; would this fanfare have scared him? The fact of the matter is that over the course of the next several years his work and his life are a blank page that neither his descendants, nor his heirs and indeed not even we are able to account for.

Did the “victory march” begin to play in his workshop; would this fanfare have scared him? The fact of the matter is that over the course of the next several years his work and his life are a blank page that neither his descendants, nor his heirs and indeed not even we are able to account for.

We do however know that he paints a great deal on the banks of the Seine and the Marne rivers, side by side with other artists, some of whom are already relatively famous. He also spends time in the Beaujolais region during school holidays, where in 1949 he buys a house in the village of Lancié, near to Villefranche sur Saône, close to where his wife Denise, who often accompanied him on his painting excursions, grew up. Later on, it is his granddaughter, who today identifies for us the exact locations of those landscapes captured on canvas or in watercolours; she readily recognizes the countryside and waterways she knew as a child. For René Teil paints his environment, what he loves, what he sees. He paints with the seasons; with assertion and refinement, he paints the reality that surrounds him.

In addition to his cherished play of light through a forest, or the limpidity of a stream, Teil enriches his work through reading and his encounters with other artists; above all painters and writers that form a sort of “geography of creation” that spans the Marne and Seine rivers, where Teil and others share this taste for nature imbued with a festive, friendly, warm simplicity that we will attempt to evoke in a later passage.

1960-1970

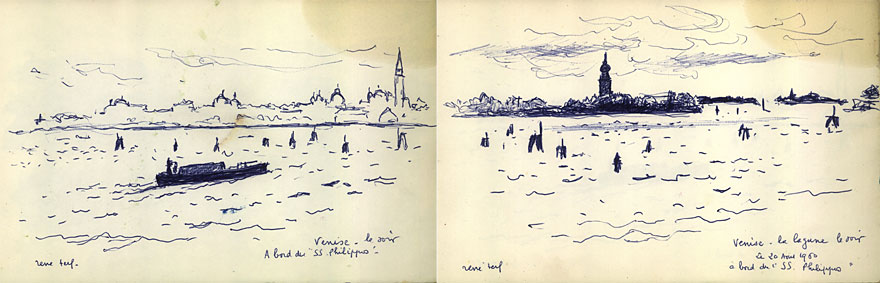

In May 1960, René Teil participates in another exhibition in Crécy-en-Brie. Other painters, including André Dunoyer de Segonzac, are at his side. He then embarks on the only overseas travel for which we have a record: elegant, lively, swift and sensitive sketchbooks map his journey through Delphi, Patras, Mykonos, Aegina and Venice during the summer of 1960.

In May 1960, René Teil participates in another exhibition in Crécy-en-Brie. Other painters, including André Dunoyer de Segonzac, are at his side. He then embarks on the only overseas travel for which we have a record: elegant, lively, swift and sensitive sketchbooks map his journey through Delphi, Patras, Mykonos, Aegina and Venice during the summer of 1960.

When autumn rolls around, Teil exhibits at the Galerie Framond in Paris from 24th November to 12th December, an exhibition for which Guy Dornand composes a highly flattering introduction:

“Seven years of absence from gallery walls, yet all the while sketches, watercolours and oils have continued to be his major concern, his main vocation…how many artists would challenge Teil’s remarkable, protective discretion with regard to an obstinate, yet substantial and noble period of work? (…) A citizen of the Briard region from birth, he preserves the legacy, recorded on canvas, of the red furrows, the brown ochre of the autumn trees, the unsullied meadows that endure invasion or mutilation by sprawling suburbs. Sixteen years after Dunoyer de Segonzac, quite a far distance from him, he grew up at the edge of the Sénart forest and it is the land of his birth that glorifies the unyielding composition, the exact colour scheme of his palette. His patient brush conjures the symphony of greenery, the dancing reflections in the Morin waters, the silhouette of country churches, the dancing roads under shifting, clear or sodden skies…he has trodden each and every path, all the old trails of a rural world where one will never reject the advice of an elder: “if the earth sticks to your shoes, leave it there!”

The critics display a lively interest in this exhibition at the Galerie Framond, as can be seen in articles that appear in “Le Peintre” (The Painter), “L’Amateur d’Art” (The Art Enthusiast), “Les Lettres Françaises” (French Letters), “Libération” and “Arts” publications. This is also the year that Teil participates in the Salon de l’Aquarelle (Watercolour Salon).

In January and then February 1961, in addition to the Salon du Dessin (Drawing Salon), he is invited to participate in two exhibitions that are held in the foyer of the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, alongside Marquet, Oudot, Planson, Chapelain-Midy and Brayer.

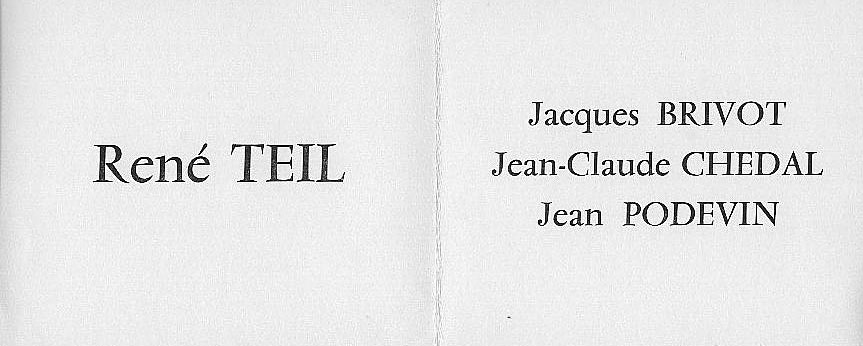

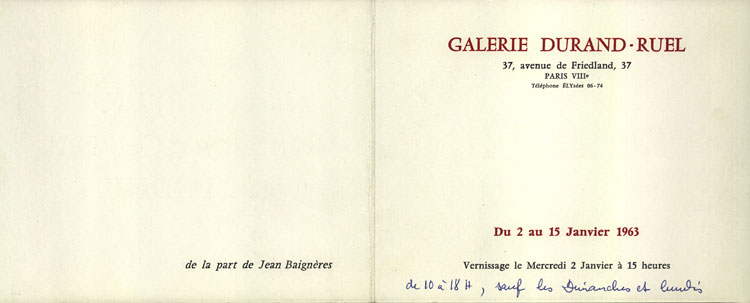

Finally, in 1963 an accolade of sorts takes place: Teil’s dealer, Jean Baignières, organises a stunning exhibition at the Galerie Durand-Ruel from 2nd to 15th January, devoted to René Teil, Jean-Claude Chedal, Jacques Brivot and Jean Podevin. In this locale, renowned throughout the History of Art, Teil is allocated an entire hall, where he exhibits seventeen canvases (Durand-Reul Archives, “Groupe Baignières” (Baignières’ Group) Exhibition: National Institute of Art History “cartons verts”).

From 1963 to 1969, exhibitions occur at regular intervals (one or two a year), occasionally held in prestigious galleries such as the Galerie Marie Louise André in Paris in May 1965, where he exhibits approximately 30 works. To mark the event, André Dunoyer de Segonzac presents him with a beautiful introduction: “healthy, direct art, devoid of formula or artifice: that is the very essence and heart of René Teil’s vast talent. A restrained and profoundly honest emotion towards nature and life. (…) Having followed his career from the beginning, I have always been struck by the continuity of his work, which has progressively increased in scope, without ever deteriorating into the easiness, the artifice and methods of the day: it is above all genuine art.”

This year is also one of major change: René Teil retires from teaching and moves to his house in Lancié in Burgundy. His wife Denise dies in November. Two years later, Teil marries Christiane Montagne, with whom he lives in Viviers in the Ardèche region until her retirement in 1969. The couple then settle permanently in Lancié.

1970-1980

Most likely because he is no longer teaching and has all the time in the world to devote to his career as a painter, Teil’s work intensifies during this decade. In 1970 alone, there are no less than five exhibitions, either solo or group, one held at the Galerie Vendôme in Paris. During this time, when he shows his works once or twice a year in various French towns, he exhibits at the Galerie Motte in Paris in 1972 and the Galerie Weil in 1974 and 1976, as well as the Galerie Malaval in Lyons in 1972, the Salon for local artists in Mâcon in 1976, where he is the guest of honour; and yet another Salon in Fontainebleau, where he donates a painting to the town in 1974. In amongst this proliferation of diverse artistic events, three significant milestones occur:

Most likely because he is no longer teaching and has all the time in the world to devote to his career as a painter, Teil’s work intensifies during this decade. In 1970 alone, there are no less than five exhibitions, either solo or group, one held at the Galerie Vendôme in Paris. During this time, when he shows his works once or twice a year in various French towns, he exhibits at the Galerie Motte in Paris in 1972 and the Galerie Weil in 1974 and 1976, as well as the Galerie Malaval in Lyons in 1972, the Salon for local artists in Mâcon in 1976, where he is the guest of honour; and yet another Salon in Fontainebleau, where he donates a painting to the town in 1974. In amongst this proliferation of diverse artistic events, three significant milestones occur:

Firstly, in 1975, a magnificent exhibition at the Musée de Villefranche-sur-Saône, where René Teil exhibits 45 paintings alongside works by the post-Impressionist artist Georges Dufrenoy (1870-1943). An obvious aesthetic connection links the two artists, as Dufrenoy had been a student at the Académie Julian, alongside Pierre Bonard, Derain, Emile-Othon Friesz, Albert Marquet and Edouard Vuillard; the two also share an affiliation with the Galerie Druet, where Dufrenoy will exhibit until 1934, when it closes its doors. Another connection between these two painters who are exhibiting together at the Musée de Villefranche: Georges Dufrenoy, like René Teil, had a personal affinity for the Beaujolais region.

Secondly, in 1977 there follows Teil’s first exhibition in a gallery that had just been opened in Belleville-sur-Saône by Marc Lacruz, a friend and neighbour. René Teil inaugurates the gallery and a professional relationship between the two men is formed. After the death of Jean Baignières in 1982, Lacruz will become Teil’s second and final dealer.

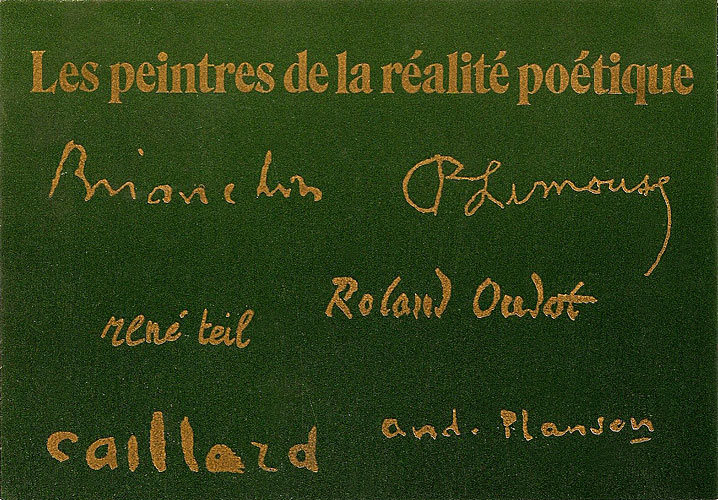

Finally, the first exhibitions in 1979 with the “Painters of Poetic Realty”, most of whom also use Jean Baignières as their dealer: Teil’s artwork travels to Switzerland, Germany and to the United States, alongside works by Oudot, Caillard, Planson, Brianchon and Limouse: Marc Lacruz will also exhibit five painters from the group along with René Teil at his gallery in Belleville-sur-Saône from April to August of this year. We will revisit Teil’s affiliation with “the Poetic Reality Group”, whose aesthetic perspective he shared quite closely.

Finally, the first exhibitions in 1979 with the “Painters of Poetic Realty”, most of whom also use Jean Baignières as their dealer: Teil’s artwork travels to Switzerland, Germany and to the United States, alongside works by Oudot, Caillard, Planson, Brianchon and Limouse: Marc Lacruz will also exhibit five painters from the group along with René Teil at his gallery in Belleville-sur-Saône from April to August of this year. We will revisit Teil’s affiliation with “the Poetic Reality Group”, whose aesthetic perspective he shared quite closely.

In 1978, when he is 68 years old and approaching the end of his life, a small pamphlet is written about the works of René Teil, in which Armand Lanoux, a writer and member of the Académie Goncourt, a friend and admirer of his work (we know that he bought artwork from Teil), writes a lengthy introduction: “…Here is a true painter that I have known for a quarter of a century and about whom the great Dunoyer de Segonzac announced (eloquently I might add) that his art is wholesome and straightforward, free from the influence of “Mannerism”. Over the years, this art grew clearer as it established itself; he was able, through the subject, to translate the inestimable weight of things. (…). René Teil’s paintings measure up to those of Dunoyer de Segonzac and Planson: dense, strong, stark and complete, an heir of Courbet and the Barbizon Masters, in tune with natural beauty as yet unmagnified, but bursting forth from the artist, compositions, still life, flowers, women, produce, vast landscapes that focused on the environment long before it became fashionable. (…) Long ago, Corot, amongst others, championed this spirit of reason. It continues to exist in René Teil’s work, proving that “the subject matter”, so beloved by painters, is the indispensable vehicle of the mind”.

1980-1985

René Teil’s final two exhibitions take place in Nantes at the Galerie Mignon-Massart in 1980, then in Troyes at the Galerie des Quais, where he exhibits seventeen paintings from 25th September to 18th October 1981. Critics agree that he is now a part of the “Painters of Poetic Reality”.

René Teil’s final two exhibitions take place in Nantes at the Galerie Mignon-Massart in 1980, then in Troyes at the Galerie des Quais, where he exhibits seventeen paintings from 25th September to 18th October 1981. Critics agree that he is now a part of the “Painters of Poetic Reality”.

Parkinson’s disease, which has afflicted him since 1977, forces Teil to stop painting in 1982. In his final works, the struggle of the painter versus the disease is manifest. René Teil dies three years later in Mâcon on 3rd September 1985. In observance of his last wishes, he is buried in Lancié beside his first wife Denise.

René Teil sold a considerable amount of artwork throughout his life: what has become of those works today?… Some are part of private collections in Europe and America, also in Morocco, but the names of the owners remain a mystery…several paintings that were bought by the State are in the state-owned furniture inventory… although we have found no trace whatsoever in any French museum.

A “Geographie of creation”

During the 1930’s and onwards, it is not unusual to meet René Teil on the banks of either the Seine or the Marne rivers, near Crécy-en-Brie. Perhaps more than any other “sur le motif” (painting in Nature) painter, he is entirely immersed in the subject; that poetry of nature which forms the fundamental epicentre of his inspiration. Throughout his life Teil remains extremely attached to the Ile de France countryside; from 1949 onwards he develops an affiliation for the hills of the Beaujolais region. He will also produce interesting Provençal landscapes from his jaunts to Saint-Tropez, where he meets Segonzac and paints at his side.

During the 1930’s and onwards, it is not unusual to meet René Teil on the banks of either the Seine or the Marne rivers, near Crécy-en-Brie. Perhaps more than any other “sur le motif” (painting in Nature) painter, he is entirely immersed in the subject; that poetry of nature which forms the fundamental epicentre of his inspiration. Throughout his life Teil remains extremely attached to the Ile de France countryside; from 1949 onwards he develops an affiliation for the hills of the Beaujolais region. He will also produce interesting Provençal landscapes from his jaunts to Saint-Tropez, where he meets Segonzac and paints at his side.

His easel and shoes are simultaneously planted in clay: “painting what is real, painting the truth, as it is ingrained in man, refusing to accept the urban soap factories of academicism that shook the painters of the Salon des refusés (Exhibition of Rejects) in the Second French Empire, the “pleinairistes” (artists who painted outdoors) and the Impressionists, and those overinflated Venus’s wafting in clouds of face powder that Zola so sneered at”, writes Armand Lanoux with regard to Teil’s painting.

From 1950, when he is not in Lancié during his holidays, Teil often spends time in Villiers-sur-Morin where he has friends who are teachers and who host him for weekends dedicated to painting. Since the mid 19th century, the Grand Morin valley has been an inspirational location for painters and this remained the case throughout the 20th century. They convened there; created meeting places, occasionally chronicled in the History of Art: and so it is that the Villiers bridge house in the heart of the Grand Morin valley is still called the “Souterrain” (Underground), an inn that was well known and valued by the artistic milieu of the time. Teil meets his painter friends there, as well as writers, critics and publishers: Armand Lanoux, Vercors, Hervé Bazin, Dominique Rollin (1952 Prix Fémina recipient), the sculptor and illustrator Bernard Milleret (head illustrator for the NRF collection published by Gallimard), all frequent the Souterrain with Teil. Degas, Derain, Man Ray, Brancusi and who knows how many others all loved their creative, festive visits to the Grand Morin valley…André Dunoyer de Segonzac in fact created a series of twelve etchings there entitled “suite du Grand Morin” (Grand Morin Series)); André Planson also lived in the area in la Ferté-sous-Jouarre; Pierre-Eugène Clairin (whose signature can be found, alongside a friendly compliment in the visitor’s book of a René Teil exhibition at the Galerie Framond in 1960) lived in Saint-Loup-de-Naud, where he invited Maurice Mourlot, who bought a house there in 1941.

And so an artistic and intellectual education is being fashioned for René Teil, an education nurtured by his encounters, his passion for literature, to which his extensive library bears witness, and friendships; firm, long-lasting, reliable friendships. “Hervé Bazin and Armand Lanoux often came to have lunch at the house” remembers Teil’s granddaughter, today the heir of his works, who lived with her grandfather at that time.

Hypotheses on a disappearance

René Teil’s body of work disappeared from memory and from the Art marketplace. His name does not appear in any internet search engine; it is missing from all auction databases. His career, that we have just retraced, offers no plausible explanation for this disappearance. The reasons therefore lie elsewhere; the following hypotheses will attempt to clarify them.

The first credible reason is provided by a network of facts: firstly, when René Teil died in 1985, he was preceded in death by Jean Baignières (his first dealer, a consummate professional) by only a few short years. Baignières was therefore no longer there to “champion” his cause. Secondly, on his deathbed, Teil asked his son André to keep his paintings alive…but his only son died prematurely one year after him aged 56. Finally, and this is perhaps the coup de grâce for the survival of this body of work, problems with the painter’s inheritance meant that for twenty four years, the bulk of artwork that he left behind remained locked away in attics; not one painting could come out, or be sold. This “deep freeze” not only prevented an active trade of Teil’s work and a maintained presence amidst the secondary market, but it also prevented Marc Lacruz, Teil’s second dealer and friend, from showing, promoting and selling René Teil’s artwork after his death.

The first credible reason is provided by a network of facts: firstly, when René Teil died in 1985, he was preceded in death by Jean Baignières (his first dealer, a consummate professional) by only a few short years. Baignières was therefore no longer there to “champion” his cause. Secondly, on his deathbed, Teil asked his son André to keep his paintings alive…but his only son died prematurely one year after him aged 56. Finally, and this is perhaps the coup de grâce for the survival of this body of work, problems with the painter’s inheritance meant that for twenty four years, the bulk of artwork that he left behind remained locked away in attics; not one painting could come out, or be sold. This “deep freeze” not only prevented an active trade of Teil’s work and a maintained presence amidst the secondary market, but it also prevented Marc Lacruz, Teil’s second dealer and friend, from showing, promoting and selling René Teil’s artwork after his death.

The second reason is no doubt linked to the “aesthetic climate” of the era: it is clear that the predilection for art in the 20th century firstly for Cubism, then abstract art, made life difficult for a great many artists, whose figurative, “sur le motif” (painting in Nature) artwork (however loosely derived from the Barbizon School), was increasingly engulfed in contempt or indifference with each passing decade. This letter from Segonzac addressed to Teil from Saint-Tropez on 18th January 1964 fully acknowledges this climate:

My dear friend,

In great appreciation for your continued sympathy and loyalty – I send my very best wishes for 1964.

I get the sense that 1963 was a disappointment to you. Clearly the era in which we are living is not a favourable one for true artists – who work with honesty and Faith. Too much bluffing, trickery, publicity stunts – often unhealthy conjecture distorts the opinion of art lovers and the general public.

Time will sort everything out. It is the most reliable of Critics. How many of the greats were subjected to a lack of understanding and were judged by their contemporaries!…

You possess a beautifully pure talent – very healthy – which maintains a hint of truth that has become quite rare in our times.

Only authentic art will survive; the artist’s untainted creation. Artificial art, reflected in the museums, the fake overkill, all that staging will one day collapse.Your old friend who holds you in the highest esteem, with much affection,

A. Dunoyer de Segonzac.

When one scans René Teil’s career, or those of the members of his “aesthetic family”, we see that things go quite well for them until the end of the 1960s. We also perceive among them a certain indifference, imbued with a lack of concern, for the looming trends and international successes of the Grand Masters of abstract art. At the beginning of the 1970’s these painters of Nature are selling poorly or not at all. Critics tend to overlook them completely and discouragement, combined with bitterness, sets in amongst them. With the exception of a few artists already famous enough to not feel the effects of this rather dismissive atmosphere (Dunoyer de Segonzac, Dufy and Brayer, to name a few), these artists begin to feel increasingly alone and isolated, they question and doubt themselves. When a René Teil exhibition is held at the Galerie Motte in Paris, the following letter from Guy Dornand, dated 1st July 1972, reproduced in its entirety, sums up this feeling of abandonment and solitude:

When one scans René Teil’s career, or those of the members of his “aesthetic family”, we see that things go quite well for them until the end of the 1960s. We also perceive among them a certain indifference, imbued with a lack of concern, for the looming trends and international successes of the Grand Masters of abstract art. At the beginning of the 1970’s these painters of Nature are selling poorly or not at all. Critics tend to overlook them completely and discouragement, combined with bitterness, sets in amongst them. With the exception of a few artists already famous enough to not feel the effects of this rather dismissive atmosphere (Dunoyer de Segonzac, Dufy and Brayer, to name a few), these artists begin to feel increasingly alone and isolated, they question and doubt themselves. When a René Teil exhibition is held at the Galerie Motte in Paris, the following letter from Guy Dornand, dated 1st July 1972, reproduced in its entirety, sums up this feeling of abandonment and solitude:

My dear Teil,

Your letter means so much to me in spite of the tacit and sadly justified (!) criticism of my failure to review you. I did come back to the Motte but you had already left. I was therefore unable to interview you, or to have a conversation. It is not Claude-Roger Marx’s harsh words that are the cause of my confusion and that compel me to question myself. Not knowing to what extent the selection of paintings represent the prevailing development of the technique you have been favouring in the past two or three years, I have no answer. The blue tones seemed to me to be less in keeping with the highly expressive, persuasive sensitivity of your Briard landscapes. However, the impression of this hurried visitor stems from the fact that you should have perhaps centred your selection on one period, one region, on smaller formats? I therefore have no objections, as the quality was present and you would be wrong to become discouraged.

It is in fact a difficult time for all those artists who do not adorn Painting and Sculpture with those crazy hats, and instead continue to respect the meaning of these worthy endeavours. We are well aware that the Marquise’s (de Pompidour) patronage will favour the excrement, growths, secretions, pus and rubbish of an absurd “aesthetic leftism”. We should therefore expect nothing from Reviews, so-called out of habit or irony and that herald nothing particularly useful, if we only forget that Mercury willingly wears the mask of Apollo. Add to this the spinelessness of so many of the wealthy, the sheep-like behaviour of so many pseudo-enthusiasts and sycophantic bureaucrats…

Conclusion: if I am still alive when you consider your next show, before you even deal with a gallery, please consider that an afternoon or an evening of exploratory dialogue about the issue could be useful – on a totally friendly, completely honest basis of course.

Please send my regards to Madame Teil.

Yours sincerely and with the greatest respect.

Dornand.

When read today, Dornand’s comments, in fact just like those of Segonzac, have an undeniably reactionary, “stick-in-the-mud” tone. One can nevertheless understand them if we stop for a moment to consider the aesthetic milieu of the era: who were the artists that had the upper hand and were displayed on the walls of Parisian galleries at the end of the sixties and into the next decade?…The Museum of Modern Art in Paris was proposing massive, beautiful retrospective exhibitions on the works of painters Pierre Soulages and Hans Hartung at the Palais de Tokyo, the sculptors Calder and Jean Tinguely were also welcomed there with pomp and circumstance, César’s compressions were bought by the State for a fortune, Vasarely was a rainmaker at the Presidential Elysée Palace where the Pompidou couple in residence at the time were furiously professing patronage and good taste (hence Guy Dornand’s earlier sarcastic reference to the marquise de Pompidour!) A little earlier, the entire Grand Palais was celebrating Cubism by elevating Pablo Picasso, who was still alive, to the enviable status of “Monument of Art History”. We therefore have a greater understanding of how René Teil and his friends, how these “little masters” (the term “little” is not meant in a derogatory way) of simple, honest poetry, felt so painfully isolated. And it would almost be an exercise in cruel, sardonic humour to wonder what they thought of the stars of contemporary art in America in those days; Andy Warhol’s tins of soup, or Jackson Pollock’s speckles, or even in the figurative genre, David Hockney’s hyperrealist artwork!…Now armed with the answer, we are better equipped to understand the isolation in which these artists lived, and why it was almost half a century before art historians, museum curators and art enthusiasts began to view these painters in a new light; painters whose only desire was to follow in a tradition passed down from Boudin or Vlaminck, who were often considered in their own era to be completely passé.

When read today, Dornand’s comments, in fact just like those of Segonzac, have an undeniably reactionary, “stick-in-the-mud” tone. One can nevertheless understand them if we stop for a moment to consider the aesthetic milieu of the era: who were the artists that had the upper hand and were displayed on the walls of Parisian galleries at the end of the sixties and into the next decade?…The Museum of Modern Art in Paris was proposing massive, beautiful retrospective exhibitions on the works of painters Pierre Soulages and Hans Hartung at the Palais de Tokyo, the sculptors Calder and Jean Tinguely were also welcomed there with pomp and circumstance, César’s compressions were bought by the State for a fortune, Vasarely was a rainmaker at the Presidential Elysée Palace where the Pompidou couple in residence at the time were furiously professing patronage and good taste (hence Guy Dornand’s earlier sarcastic reference to the marquise de Pompidour!) A little earlier, the entire Grand Palais was celebrating Cubism by elevating Pablo Picasso, who was still alive, to the enviable status of “Monument of Art History”. We therefore have a greater understanding of how René Teil and his friends, how these “little masters” (the term “little” is not meant in a derogatory way) of simple, honest poetry, felt so painfully isolated. And it would almost be an exercise in cruel, sardonic humour to wonder what they thought of the stars of contemporary art in America in those days; Andy Warhol’s tins of soup, or Jackson Pollock’s speckles, or even in the figurative genre, David Hockney’s hyperrealist artwork!…Now armed with the answer, we are better equipped to understand the isolation in which these artists lived, and why it was almost half a century before art historians, museum curators and art enthusiasts began to view these painters in a new light; painters whose only desire was to follow in a tradition passed down from Boudin or Vlaminck, who were often considered in their own era to be completely passé.

Finally, the third explanation which can in part clarify the obscurity into which René Teil disappeared was perhaps his personality and his lifestyle. René Teil was a teacher, and as a result he did not need to sell his artwork to make a living. Moreover, he seemed to enjoy this profession and in his own mind this never conflicted with his career as a painter, in spite of all the faith and energy he afforded it during his life as an artist. On the contrary, by freeing his painting from the obligation of financial return, teaching provided him a freedom of tone and decisiveness as an artist which he greatly leveraged: always free and independent, never formally linked to anyone in particular, alone with his brushes and canvases, never integrating into any group, movement or clique, he lived out his career in a sort of isolation and indifference to success, highlighted by his “regional” side, his wily and sometimes openly apprehensive solitary personality. He never even fully confided in his dealer, Jean Baignières, whom he liked and trusted, and never formally gave him exclusive rights, as this letter dated 15th August 1978 clearly indicates:

My dear Teil,

As agreed, I am writing to you after your earlier telephone call. Here is an objective overview of how things lie: I have no qualms in saying, and I fear that painters believe that I say this purely with my own interests at heart, that it is extremely important for their social standing that they are believed to have entered into an exclusive contract with a dealer and in order to obtain his artwork, it must be through that dealer.

It is because of this that Oudot, for example, is in the position he now enjoys, a situation that is vastly superior to that of some of his contemporaries who did not understand how things work.

As I am not yet in a position to purchase your entire body of work, you must play the game and say that I am your intermediary.

In the case of the Dutch dealer that you spoke of, I have a suggestion: give me his name and address and let him know that I will be in touch. Per painting, I will quote him a price that is twice what you quote me. In the case of a sale, as the paintings belong to you, you will earn ¾ of that asking price, and I will earn ¼.

I will handle all the transport costs with the dealer, as well as insurance and customs formalities.

This process proved beneficial to all involved in a recent transaction with a Swedish dealer who was sent to me by Oudot.

One important detail: I can tell the Dutchman that it was Segonzac who, as you know, encouraged me to become an art dealer and who advised me to take an interest in you.

Jean Baignères.

This letter reveals an astonishing haggling process between these two men, who had nevertheless worked together for thirty one years! Teil’s somewhat timid personality (“grandfather was difficult to deal with”, remembers his granddaughter; “Teil was reclusive and taciturn”, confides Marc Lacruz) which perhaps cost him the path to posterity by prompting him to keep his distance from the Painters of Poetic Reality, painters with whom, in addition to collaborative exhibitions, he obviously shared aesthetic affinities. In order to understand Teil’s relationship with this group, which today appears to us to be an episode of “ships passing in the night”, let us consider it further. This completely informal group of Painters of Poetic Reality originated from a book, published by Gisèle d’Assailly, about eight painters that she liked. Writer, journalist, President of Editions Julliard from 1962 to 1964, Madame d’Assailly’s well-written book, enhanced with a long preface by Claude-Roger Marx, an influential art critic of the era, was successful. Close friends with one of the painters, she met other painters known to her friend, who in turn introduced her to their friends; a series of articles concerning their work turned into a book entitled: “Avec les peintres de la realité poétique” (Alongside the Painters of Poetic Reality). The book enjoyed great success, to the extent that as a result, an eponymous group was born for critics, and later art historians; a group basically created around the heartwarming adage: “the friends of my friends are my friends”! One can therefore speculate that if perhaps one of the group had introduced Teil to Gisèle d’Assailly, he would have naturally integrated into this group initiated by the publication of a book…and he would be a part of the History of Art that today comprises the eight companions of Poetic Reality: Brianchon, Caillard, Cavaillès, Legueult, Limouse, Oudot, Planson and Terechkovitch.

This letter reveals an astonishing haggling process between these two men, who had nevertheless worked together for thirty one years! Teil’s somewhat timid personality (“grandfather was difficult to deal with”, remembers his granddaughter; “Teil was reclusive and taciturn”, confides Marc Lacruz) which perhaps cost him the path to posterity by prompting him to keep his distance from the Painters of Poetic Reality, painters with whom, in addition to collaborative exhibitions, he obviously shared aesthetic affinities. In order to understand Teil’s relationship with this group, which today appears to us to be an episode of “ships passing in the night”, let us consider it further. This completely informal group of Painters of Poetic Reality originated from a book, published by Gisèle d’Assailly, about eight painters that she liked. Writer, journalist, President of Editions Julliard from 1962 to 1964, Madame d’Assailly’s well-written book, enhanced with a long preface by Claude-Roger Marx, an influential art critic of the era, was successful. Close friends with one of the painters, she met other painters known to her friend, who in turn introduced her to their friends; a series of articles concerning their work turned into a book entitled: “Avec les peintres de la realité poétique” (Alongside the Painters of Poetic Reality). The book enjoyed great success, to the extent that as a result, an eponymous group was born for critics, and later art historians; a group basically created around the heartwarming adage: “the friends of my friends are my friends”! One can therefore speculate that if perhaps one of the group had introduced Teil to Gisèle d’Assailly, he would have naturally integrated into this group initiated by the publication of a book…and he would be a part of the History of Art that today comprises the eight companions of Poetic Reality: Brianchon, Caillard, Cavaillès, Legueult, Limouse, Oudot, Planson and Terechkovitch.

The relevance of this question may be assessed when reading Claude-Roger Marx’s introduction to Gisèle d’Assailly’s book: “The assemblage of these portraits is no coincidence; on the contrary, they are inextricably linked. The camaraderie or professional ties that united these eight painters were such that, having discovered first one of them she (Gisèle d’Assailly, author’s note) was driven, in her affinity for each and every one of them, to sum up a generation. A plethora of similarities in disposition, character, or technique gave her the impression, when visiting one workshop to the next, that the climate remained unchanged, no matter how different the location or the setting, the welcome, the shaking of hands, or the smiles. Whether dealing with someone middle class, with a bohemian, a traveller or a homebody, she witnessed the same queries, the same demands and parallel solutions. Today’s discovery further enhances the pilgrimage once made to the four corners of Paris; everything down to the slightest distinctions, the very contrasts in inspiration in the craft that were highlighted through comparison and enticed this visitor through her book to once again unite these contemporaries as they often were by the Salon des Indépendants (Salon of Independent Artists), at the Tuileries, at the Salon d’Automne, in the small galleries, or more soberly, on museum walls”.

The relevance of this question may be assessed when reading Claude-Roger Marx’s introduction to Gisèle d’Assailly’s book: “The assemblage of these portraits is no coincidence; on the contrary, they are inextricably linked. The camaraderie or professional ties that united these eight painters were such that, having discovered first one of them she (Gisèle d’Assailly, author’s note) was driven, in her affinity for each and every one of them, to sum up a generation. A plethora of similarities in disposition, character, or technique gave her the impression, when visiting one workshop to the next, that the climate remained unchanged, no matter how different the location or the setting, the welcome, the shaking of hands, or the smiles. Whether dealing with someone middle class, with a bohemian, a traveller or a homebody, she witnessed the same queries, the same demands and parallel solutions. Today’s discovery further enhances the pilgrimage once made to the four corners of Paris; everything down to the slightest distinctions, the very contrasts in inspiration in the craft that were highlighted through comparison and enticed this visitor through her book to once again unite these contemporaries as they often were by the Salon des Indépendants (Salon of Independent Artists), at the Tuileries, at the Salon d’Automne, in the small galleries, or more soberly, on museum walls”.

Whether the question of René Teil belonging “virtually and posthumously” to the Poetic Reality Group holds any validity, the fact remains that his affiliations with this group were real.

Whether the question of René Teil belonging “virtually and posthumously” to the Poetic Reality Group holds any validity, the fact remains that his affiliations with this group were real.

Firstly, because Jean Baignières was a dealer for almost all these painters at one time or another. This explains why the invitation for the exhibition organised in 1979 by Marc Lacruz at his gallery in Belleville-sur-Saône entitled: “les peintres de la realité poétique” (Painters of Poetic Reality) contained reproduced signatures of Brianchon, Oudot, Caillard, Planson and Teil. “Because Jean Baignières was his official dealer, I asked him permission to exhibit René Teil” explains Marc Lacruz. “And he was the one who suggested incorporating artwork from painters in the Poetic Reality Group, for whom he was the dealer, into this exhibition.”

Secondly, because the very same Jean Baignières was responsible for shipping Teil’s work, alongside that of the Poetic Reality Group, to exhibitions in Europe and the United States.

Secondly, because the very same Jean Baignières was responsible for shipping Teil’s work, alongside that of the Poetic Reality Group, to exhibitions in Europe and the United States.

Finally, the heterogeneous nature of this group (a somewhat congenital nature if one recalls the circumstances of its creation), is such that from an aesthetic standpoint, Teil would have naturally taken his place alongside the great Cavaillès, Limouse and Planson, and to a lesser extent within proximity of Brianchon and Caillard. Let us venture a final hypothesis: is it a possibility that the work of Oudot, Legueult and above all Terechkovitch in fact dissuaded Teil from a more formal integration into “Poetic Reality”…?

By presenting the discovery of this forgotten artist to Art historians, museum curators, critics and collectors, we are simply attempting to fill out and endorse this remark addressed to Teil by André Dunoyer de Segonzac in one of his letters: “Time will sort everything out. It is the most reliable of Critics”.

Alain Dunoyer de Segonzac

Today, the important body of work left by René Teil belongs in its entirety to his granddaughter, Madame Renée Beucher, née Teil. It is at present for the most part itemised, localized catalogued, dated and photographed. The archives collected on René Teil and his era are documented and listed.

____________________________

Contributors:

Author: Alain Dunoyer de Segonzac

Research and material processing: Florence Duhamel

Family archives: Renée Beucher

Photographic documentation of the body of work: Daniel Beucher

Iconography: Gilles Carmine

Artwork photography: Roy Cutts

Publisher: Atelier Gilles Carmine

Digital publication: Juan Clemente

PDF design: Audrey Julien

English translation: Lisa Dunoyer

With thanks for their generous contributions: Madame Inès Champetier de Ribes (née Baignières); Marc Lacruz, art dealer, Edouard Vasseur, head of the archive team at the Ministry of Culture and Communication; Yann Onfroy and Marianne Brabant, Decorative Arts library; Flavie Durand-Ruel and Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel Gallery archives.

© Text: Alain Dunoyer de Segonzac and Florence Duhamel. Registered with the Société Des Gens De Lettres de France, December 2009

© Photos: Alain Dunoyer de Segonzac, Florence Duhamel, Roy Cutts